Thirty years ago, Wayne M. Hypes, one of my heroes and a mentor in soil conservation, came into my USDA office in Verona, Virginia, and gave me a wooden candleholder. It was no ordinary candleholder: It was made from American Chestnut, historic wood from a forgotten past. At that time Wayne was a director on the board of the Headwaters Soil and Water Conservation District (HSWCD).

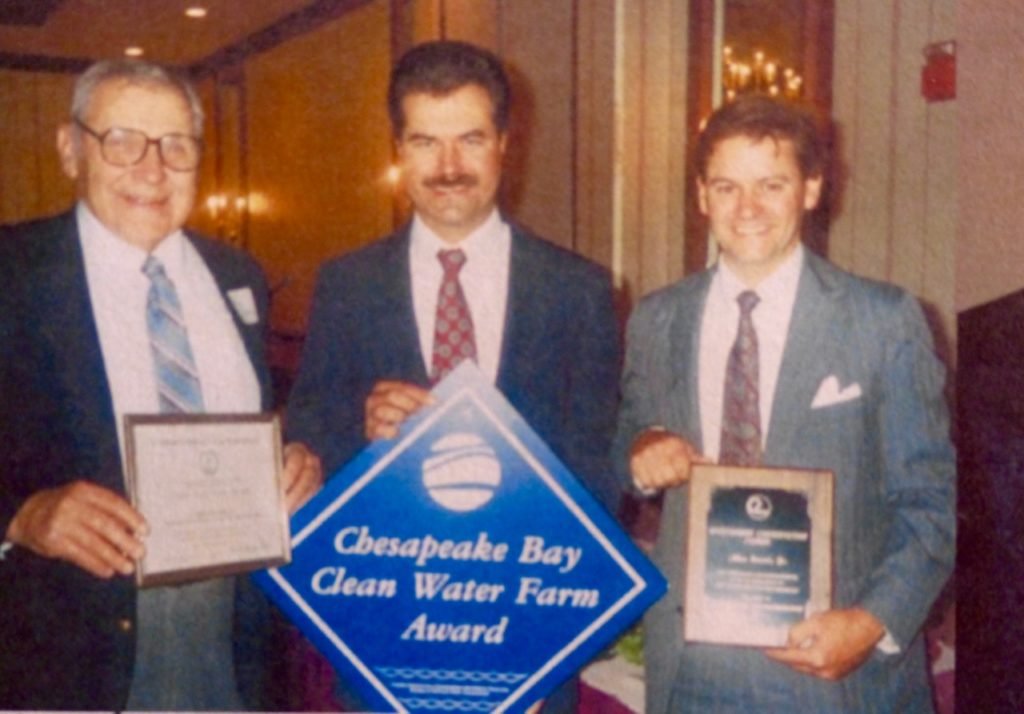

Wayne M. Hypes (left), director for the HSWCD, and Bobby Whitescarver, district conservationist for USDA (right) give Allan Bocock Jr. his award for outstanding conservation circa 1990. Photo credit VA NRCS

America’s Greatest Tree, the American Chestnut

As he handed me the candleholder, he said, “I made this out of an American Chestnut rail from our family farm in Craig County. I helped my father drag the logs out of our woods with horses. We split the logs into rails to make fences on the farm. I went back to the farm and got some of those old rails and made candleholders out of them. This one is for you.”

This is the candleholder that Wayne Hypes gave me that he made out of American Chestnut wood from his farm in Craig County, Virginia. Photo credit R. Whitescarver

When I look back on that moment and feel the candleholder in my hands, I think of Wayne’s generosity, the legacy of a tree that was once America’s greatest, and the tragedy that unfolded in a mere 50 years. The tree that made the wood for my candleholder sprouted most likely before 1800. I was holding more than 200 years of history in my hands.

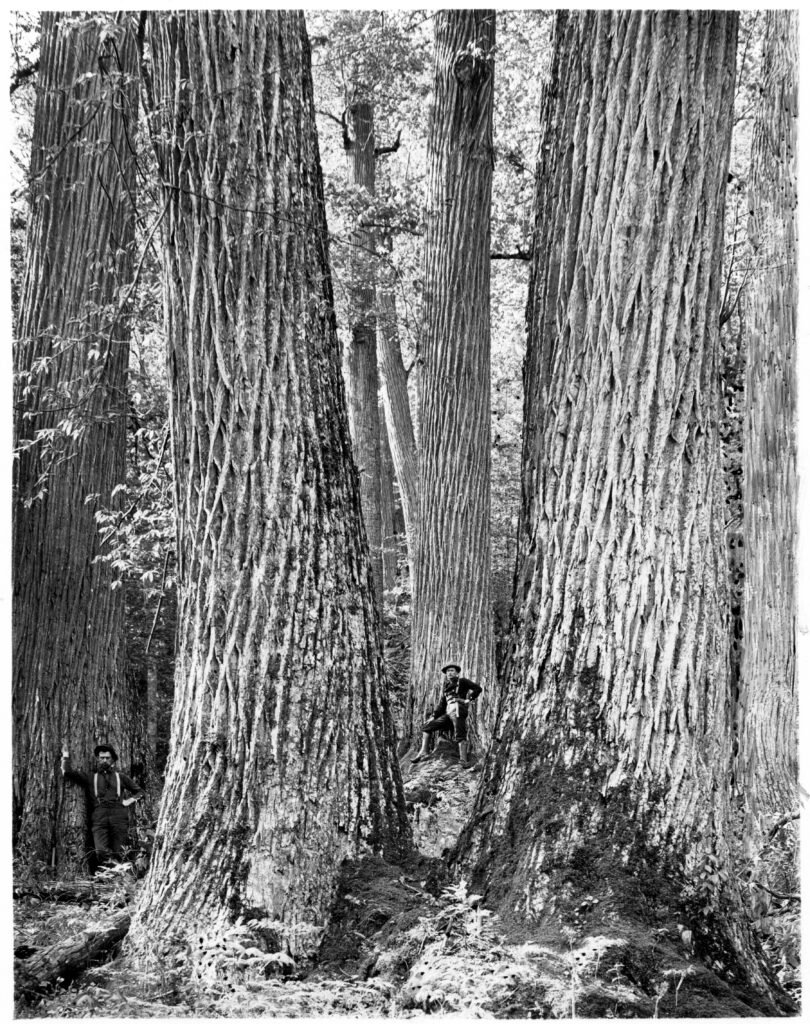

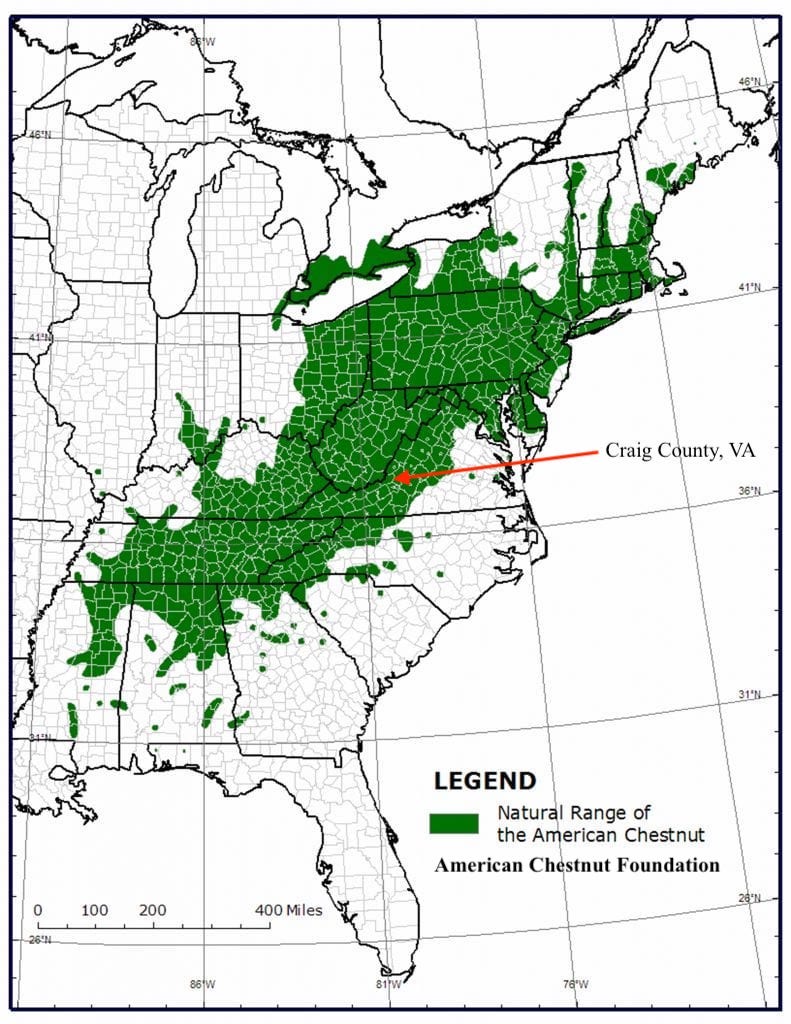

In 1900, the American Chestnut was the tallest, fastest-growing, and most dominant tree in the Appalachian forest, making up one in every four trees. It was the anchor of every community in its range, providing lumber to build homes and businesses; nuts for humans, livestock, and wildlife to eat; tannins for making leather. Those trees, the tallest in the forest, provided ecosystem services like cleaning air and water and providing wildlife habitat.

An Invasive Foreign Fungus Attacks American Chestnut Trees

In 1904, in the New York Zoological Park, a lethal fungus from China was discovered that would infect every single Chestnut tree, and by 1954 the trunks, branches, and stems of almost every tree were all dead (the fungus doesn’t kill the root). The infection and the subsequent death of the trees were referred to as the chestnut blight. It is often considered the greatest natural resource disaster in American history.

Wayne was born in 1920. By that time the fungus was spreading from its source in New York to many parts of the range. My mentor grew up on a farm in the Sinking Creek Valley of Craig County, Virginia, in the heart of the range of American Chestnut. He must have been fond of the giant trees on his farm, most of them towering over 100 feet tall, and I’m sure he enjoyed the sweet flavor of its bountiful nuts.

When he started college at Virginia Tech in 1938, he must have noticed the march of death of his beloved trees. The Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. Wayne had recently graduated from Virginia Polytechnic Institute (now Virginia Tech) but was too young to receive his commission in the United States Army. Instead, he joined the Civilian Conservation Corps and worked with the corps until he was old enough to fight in the war. When he turned 18, he got his commission as a second lieutenant and immediately went to fight the Japanese in the South Pacific. It must have broken his heart when he returned to find the mountains brown with dead trees and all the towering giants on his farm dead.

Wayne M. Hypes, soil conservationist, soldier, American Chestnut lover, died in 2005.

In Search of Resistance

There has been an epic and heroic quest to bring back the American Chestnut ever since the dreaded fungus was discovered. Devoted tree lovers seek out the elusive trees that have survived the blight. Scientists can use their nuts to continue selecting for disease resistance. A few trees are still standing such as the one in Amherst County, Virginia. Susan Freinkel, the author of American Chestnut: The Life, Death, and Rebirth of a Perfect Tree, describes the tree as “an aging champion struggling to stay upright until the last round.”

A surviving true American Chestnut in Amherst County, Virginia, April 12, 2021. Photo credit Wim Brinkerink

The Thompson Tree—Born from Nuclear Irradiation

There’s one tree that has achieved the most disease control in America, according to plant pathologist Dr. Gary Griffin of Virginia Tech. Called the Thompson Tree, it resides in the Lesesne State Forest in Nelson County, Virginia.

It stands alone with a rickety fence around it on the eastern slope of Three Ridges Mountain. In the 1950s during an initiative that then-president Eisenhower called “atoms for peace,” Albert Dietz irradiated thousands of chestnut seeds with Cobalt 60. Many of those seeds were planted at Lesesne State Forest. Few survived, but on one of the surviving roots Dr. Griffin and Tom Dierauf, chief of forest research with the Virginia Department of Forestry, grafted two sprigs from a resistant native in Appomattox County, Virginia. Those two sprigs are the largest tree trunks in the background of the picture below.

Dr. John Scrivani (center) and my JMU students in front of the Thompson Tree—a historic American Chestnut. Photo credit R. Whitescarver 2014

Rebirth of the Perfect Tree

How do we beat the blight and restore the tree? The American Chestnut Foundation names three main strategies: breeding, biotechnology, and biocontrol. The most promising effort so far has been to breed resistance into the tree. The Chinese Chestnut is resistant to the fungus. Scientists with the American Chestnut Foundation use a method called back-cross breeding by which they cross-pollinate a true American Chestnut with a true Chinese Chestnut, which results in a hybrid that is half American and half Chinese. They then back cross this hybrid with true American Chestnuts, selecting for resistance until they achieve a Chestnut that is 15/16 American and 1/16 Chinese. This work takes decades of patience and dedication.

Restoration American Chestnut. Notice the wave-like serrated edge of the leaf. This is typical of American Chestnut.

Restoration American Chestnut 1.0

The result of the back-cross breeding process is called a Restoration American Chestnut 1.0. By joining the American Chestnut Foundation, you can support its research and acquire Restoration American Chestnut seeds to plant. In 2016 I planted several of the nuts.

Me, holding my grandson, and my son, Neal, with a Restoration American Chestnut 1.0 I planted in 2016. The picture was taken in 2017. Photo credit J. Hoffman

I received four nuts this year and will plant them on our farm at Whiskey Creek Angus in Churchville, Virginia.

Forty years of science and passion went into this Restoration American Chestnut 1.0 seed that just germinated. Acquire your seeds today from the American Chestnut Foundation. Photo credit R. Whitescarver

In addition to Freinkel’s book linked above, another great read about the tree, with lots of pictures and stories, is Mighty Giants, An American Chestnut Anthology, by Chris Bolgiano.

Reverence for Wood

I cherish the wooden candleholder Wayne made for me. It’s in a prominent place in our home, and every time I look at it, I think of the good times we had together, the legacy of America’s greatest tree, and the dedication of all the people restoring it to the forest.

34 Comments

Leave your reply.